Copyright 2009 by Gary L. Pullman

Although cartoonists, illustrators, stand-up comedians, and comedic television and movie stars are not literary humorists per se, they have contributed to the form and have much to offer those who would adapt their techniques to the needs and purposes of literary humor. Included in this group of humorists are cartoonists and illustrators such as James Thurber, Charles Schultz, Greg Evans, Gary Larson, Chic Young, and Norman Rockwell; situation comedy writers; standup comedians such as Lenny Bruce, Red Skelton, Jay Leno, David Letterman, Woody Allen, Rodney Dangerfield, Flip Wilson, and Jonathan Winters; television and movie stars such as Lucille Ball, Carol Burnett, W. C. Fields, Groucho Marx, Charlie Chaplin, Bill Cosby, Roseanne, Jerry Seinfeld, and Ray Romano.

Typically, cartoons are either single-panel or multiple-panel illustrations. Single-panel cartoons, which may not, but more typically do, include a caption, or line of text, at the bottom (often to deliver the punch line, or the point, of the joke), portray a simple, humorous situation. Multiple-panel cartoons often consist of three panels, in which the first sets up the situation, the second makes a commentary on the situation, and the third delivers the punch line. However, multiple-panel cartoons can also consist of one, four, or some other number of panels. Normally, with regard to newspaper cartoons, or comics, the daily strips are one-panel or three-panel, with the Sunday versions running to several panels which depict and narrate more complicated jokes and humorous situations.

There is a great competition among cartoonists. There is a limited market, even with the hundreds of newspapers and magazines published weekly, monthly, quarterly, semi-annually, and annually in the United States and elsewhere, and there are many talented illustrators and writers vying for the available space. Therefore, a cartoonist must find a slant, a topic, or an approach that will connect with a sizeable body of readers but, at the same time, will be unique or at least different enough from the usual fare to earn his or her work a place among the many strips that are already being printed on a regular basis. Competition among such humorists has enriched the genre of humor writing for cartoonists and other humorists, as it has for their readers as well.

We have sought to capitalize upon the competition among cartoonists and other illustrators by selecting a few, past and present, whose works exemplify the diversity within the field and, at the same time, have had staying power with fans. By discerning the techniques and methods of such humorists, one can expand his or her own concept and understanding of humor. J

ames Thurber, a cartoonist on the staff of

The New Yorker, drew simple cartoons in a wavering hand. He had poor eyesight, which failed more and more as he aged, and his fluttery drawing style reflected his poor vision. It also happened to complement his vision of the world, which was surreal and fantastic, rather than realistic or mundane. Fellow humorist Dorothy Parker described Thurber’s drawings as resembling “unbaked cookies,” and Thurber himself admitted that others likened them to illustrations drawn under water.

Like many other humorists, Thurber fictionalized his own experiences in plotting his short stories and cartoons, many of which are collected in

My Life and Hard Times. Such stories as “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty” and “The Cat-bird Seat,” like his

Fables For Our Time are well-known examples of his work, as are cartoons he frequently published in

The New Yorker.

He drew and wrote of ordinary people who sought to escape the tedium of everyday life, often through imaginative flights and fancies. Often, his protagonists are shy, timid men who long to live heroic lives or milquetoasts who wish that they, not their wives, ruled their roosts.

His

Is Sex Necessary? or,

Why You Feel the Way You Do is a send-up of self-help psychology books (as is Bombeck’s

Aunt Erma’s Cope Book). Thurber also wrote several books of contemporary, satirical fables with punch lines instead of morals.

Children are a popular theme among cartoonists.

Charles Schultz, who drew the

Peanuts comic strip, peopled his work with such well-known characters as Charlie Brown and his kid sister Sally, Lucy van Pelt and her little brother Linus, Pig-Pen, Woodstock, and Charlie Brown’s pet beagle, Snoopy. Although he himself claimed to be a “secular humanist,” Schultz was brought up in the Lutheran faith, and Robert L. Short detected enough of the Christian worldview in Schultz’s work to write

The Gospel According to Peanuts. Since millions of the strip’s readers, both in the United States and worldwide, are either themselves Christians or are, like Schultz, familiar with and, perhaps, influenced by, Christian theology and doctrine, it is likely that this religious and cultural subtext adds to the strip’s universal appeal, as does the fact that Schultz’s “gospel” is never presented in a heavy-handed fashion but remains subtle and nuanced, as most do not want a side order of sermon with their humorous fare.

Peanuts was also popular because of the characters themselves. Each of them, it might be argued, is, in his or her own way, archetypal, representing various personas of the reader’s own self. Like Charlie Brown, we are all shy and clumsy; we are all put-upon “losers” more often than we are winners--or apt to feel that we are--and, yet, eternal optimists, we remain determined, believing that, somehow, this time, to kick the elusive football. Likewise, we, like the arrogant and self-absorbed Lucy, can be cynical and cruel, bullying and insensitive, loud and loutish. There is also a bit of the compassionate and caring, nurturing Linus in all of us. We are all these characters, at times, overtly or covertly, just as there are elements of the loyal Sally Brown, the artistic Schroeder, the neglected Pig-Pen, and the dominant-submissive, aggressive-passive duality of the Patricia (“Peppermint Patty”) Reichardt and Marcie duo. Humor with which we can identify personally is appealing to us, even when--or, perhaps, especially when--it points out our foibles and our follies, if it does so in a gentle and tolerant manner.

The relationships between the various

Peanuts characters also make the strip--and its humor--attractive. Charlie Brown, who is arguably the strip’s central character--has many friends in his community, despite his awkward, shy demeanor and his low levels of confidence and self-esteem, and he is often matched up against Lucy van Pelt, Linus van Pelt, and the Little Red-Haired Girl upon whom he has a crush. Likewise, there is a one-sided, budding romance between Lucy and Schroeder, and Lucy often is paired against her brother Linus, Charlie Brown, or Snoopy.

The strip also features running gags (humorous themes or situations that frequently snowball as they are repeated and varied over time) such as Lucy’s operation of a “Psychiatric Help” booth, from which she dispenses self-help wisdom for a five-cents fee; Charlie Brown’s attempts to kick a football that Lucy holds for him and always jerks away at the last instant; Charlie Brown’s unsuccessful attempts to fly a kite, only to have it fall victim to another “kite eating tree” or some other mishap; Lucy’s unrequited love for Schroeder, who cares only for Beethoven and his piano; and Linus’ annual attempts to greet The Great Pumpkin as it rises from the pumpkin patch to deliver gifts to girls and boys throughout the world, only to have his hopes dashed, once again. (Persistence in spite of dashed hopes is a major theme of the strip as a whole.)

Greg Evans, the creator of the newspaper comic strip

Luann, often involves his protagonist or other characters in crushes: Luann long sought to land her heartthrob, Aaron Hill, or to decide whether she likes Aaron, nerdy Gunther Berger, or suave Miguel Vargas better. Aaron himself had a girlfriend, Claudia, but that didn’t stop him from flirting with Luann, Tiffany Farrel, and other girls. Likewise, Luann’s brother Brad seems eternally to court fellow firefighter Toni Daytona, although, prior to her, he briefly dated other girls, including Diane. As often as not, once the teens hook up, they break up, as Aaron and Claudia did, as Brad and Diane did, and as Luann’s friend, Bernice Halper, and Zane did. Teen romance is one of the strip’s backbones, but the conflicts that arise between the characters also unify the strip. Much of the conflict results from Tiffany’s narcissistic interest in herself and her rivalry with Luann over boys.

Toni’s former boyfriend Dirk stalks Toni, whom he abuses emotionally, and attacks Brad. Ann Eiffel, a feminist and Bernice’s former employer at Borderline Books, caused a riff between Bernice and Zane when she became jealous of Zane. It was implied that Ann was herself infatuated with Bernice. The strip’s villains represent the types of threats that Evans sees as menacing teens and young adults and these dangers and risks also help to bring additional unity to the strip’s otherwise rather episodic character.

Gary Larson’s now-defunct single-panel strip,

The Far Side, provided an offbeat, even bizarre, take on ordinary life, delving beneath the accepted and the “real” to show the absurd, the fantastic, the bizarre, and the eerie underbelly of human experience. Many strips feature anthropomorphic animals--cows are a favorite of Larson’s--presumably because they, being animals rather than humans, can get away with saying and doing things that people could not do without annoying or offending readers and because there has always been something innately amusing about casting animals in the roles of human beings. In one strip, Larson featured a boy attempting to enter The School of the Gifted by pushing a door, despite the presence of a sign indicating that the door must be pulled to be opened. In another cartoon, labeled “A Pigeon’s View of the World,” humans were shown from above, a bull’s-eye painted atop their heads.

The use of chickens, chimpanzees, cows, dogs, and other animals as stand-ins for humans has not always let Larson off the hook in depicting situations that some readers found too gory, politically incorrect, or otherwise offensive to some readers. One that caused controversy hinted at bestiality between ethnologist Jane Goodall and a chimpanzee. While being groomed by his mate, the female chimpanzee finds a human hair in the male’s coat, and asks, rather archly, one imagines, “Conducting a little more 'research' with that Jane Goodall tramp?”

Although humorists are given much wider leeway in making jokes or telling anecdotes than is the case with ordinary men and women, there is a limit even on what readers will accept from such once “all-licensed fools,” as we shall see even more clearly when we discuss the David Letterman-Sarah Palin controversy concerning Governor Palin’s 14-year-old daughter, Willow.

Chic Young created the

Blondie comic strip, which, like many newspaper comics, spawned a movie. This strip, which began in 1930, originally featured a spunky, independent young flapper with golden locks named Blondie Boopadoop and her raccoon coat-clad, pork-pie-wearing boyfriend, Dagwood Bumstead. Over the years, as times changed, they traded in their Roaring Twenties togs for more contemporary clothing, Blondie became a stay-at-home mother, raising two children, and a dog, Daisy, completed their happy family. Meanwhile, Dagwood went to work as an executive for J. C. Dithers Construction Company. The strip’s props show the passage of time by constantly updating the characters’ allusions, dress, and possessions, Dagwood, for example, buying a flat-screen monitor for his home computer and foregoing the wearing of a hat and garters for his socks.

A cavalcade of other characters were added, including son Alexander and daughter Cookie; Mr. Beasley, the postal carrier who collides with Dagwood every morning as, late for work again, Dagwood rushes to meet his fellow carpool participants; the Bumsteads’ neighbor, Herb Woodley, with whom Dagwood plays an occasional round of golf, and Herb‘s wife, Tootsie; Dagwood’s boss and colleagues; the pesky neighbor boy Elmo Tuttle; Mr. Dithers’ wife, Cora; and the owner of Lou’s diner. In addition, Blondie has started her own catering business.

Like many other comic strips,

Blondie features a number of running gags: Dagwood’s famous sandwiches, sofa naps, collisions with Mr. Beasley, Dagwood’s interrupted baths, Dagwood’s being fired by Mr. Dithers (only to be rehired when the boss cools off), Dagwood’s insomnia, Dagwood and Blondie seated in armchairs that face in different directions while they occupy themselves with separate pastimes or tasks, Dagwood’s chronic lateness to work; Dagwood’s having to run to catch the carpool vehicle, and Dagwood’s demand for a salary increase that Mr. Dithers refuses to honor.

From

Blondie, humorists can learn both the need to keep humor contemporary and the techniques by which to do so. By staying current with the changes that come with changing times, the strip retains its relevancy and appeal as new generations are introduced to the strip. Were its creator and present staff to ignore such changes, it is like that their strip would soon become as obsolete as Blondie’s flapper togs or Dagwood’s raccoon coat. In addition, new characters keep the strip fresh, while the familiarity of recurring characters and running gags make readers feel as if they know the Bumsteads and their acquaintances.

Norman Rockwell is not a name that one necessarily associates with humor, although many of his paintings--and not merely those that depict April’s Fools states of affairs--depict humorous situations. His is a gentle sense of humor, teasing a smile of recognition from his admirers rather than a sense of outrage, annoyance, chagrin, or embarrassment. We laugh at the boy who, standing upon a chair, his pants and underpants pulled half way down, anxiously peruses the diploma of the family doctor who, loading a hypodermic syringe, is about to administer a shot, for we ourselves have been in the boy’s place and understand his apprehension.

Likewise, we identify with the plight of the young runaway, his knapsack laid on the floor beside his stool as he sits beside the policeman who has napped him treats him to an ice cream sundae; with the sailor who visits a tattooist to have the latest of his girlfriends’ names added, above a series of cross-out feminine names, below it; and with the worry of the little girl who watches the family physician as he listens intently to her doll’s chest through his stethoscope.

Rockwell’s humor touches the heart, capturing the simple, sincere emotions of the young and old, depicting, for his generation, the essence of marriage, family, patriotism, love, and faith, his art showing that humor can be gentle and subtle and tender and nostalgic, or even melodramatic, just as it can be sardonic, caustic, and satirical. Certainly, it can be primarily visual as well, as he and other artists have demonstrated.

We can learn from humor, wherever it occurs, and, for this reason, humorous advertisements should not be overlooked. Rockwell painted many himself, although none were as sassy and sexy as many of the ones that appear in today’s magazines.

Because magazine advertisements are more visual than linguistic in their communication of their messages, it is helpful to know the techniques by which they communicate their meanings. Otherwise, their messages may be perceived unconsciously, without one being aware of how he or she is being manipulated. Many advertisements use humor to get their messages across, and, by understanding the means of indirect communication that an advertisement employs, the reader can better appreciate both the act of communication itself and the advertisement’s humor.

As is the case with regard to other commercials, a printed advertisement’s purpose is to sell a product or a service. However, they often seem to be about something else, such as an emotion or an experience. Such advertisements imply that the product or service will make the buyer feel a certain way or have a particular experience. The emotion or experience is apt to be pleasurable and desirable. By equating the product or the service that is being advertised with such an emotion or experience, the advertisement attempts to persuade its viewer to purchase the commodity.

The language that advertisers use is primarily visual; however, it also includes minimal text. The text is usually the key to the meaning of the advertisement, suggesting how the drawing or photograph should be interpreted. Many times, the text uses a pun, or play on words, as a clue to how the visual component of the advertisement should be understood. The advertisement’s text, which may be no more than a caption, a phrase, or, sometimes, even a word, typically uses such rhetorical devises as allusions, double-entendres, metaphors or similes, and symbolism to convey the meaning of the advertisement’s image. In reading an advertisement, it is usually best to start with its imagery, or the visual component of the advertisement. In doing so, keep in mind that everything in an advertisement is planned. Nothing is there by accident.

Advertisements cost hundreds, thousands, or, in a few cases, even millions of dollars. Because they are expensive and because advertisers want to sell their products or services, every detail of an advertisement is carefully designed. Nothing is left to chance. Therefore, in reading an advertisement, one should consider every detail, both individually and in relation to one another and to the advertisement as a whole.

Most advertisements feature one or more models. When there is more than one model, the figure who is nearest to the center of the advertisement (and, often, the one who is also bigger or who stands out in some other way) represents the advertisement’s central focus. It is with him or her that the advertiser wants the viewer to identify. The advertisement invites the viewer to imagine that he or she is this figure. Besides placement and size, the advertisement’s central figure can be made to stand out from other models by being shown in the brightest area of the picture, by wearing colorful or fashionable costume while the others are wearing plainer costume, by having other models’ gazes focused on him or her, by smiling while others are not smiling, and by many other ways. However the advertisement makes the central figure stand out from other models, the technique will involve contrast. By making him or her look different than everyone else in the picture, the advertisement highlights him or her.

In reading an advertisement, ask yourself how and why the main figure stands out from others. Consider everything you can think of concerning the central figure. Is this model male or female? Older or younger? Wealthy, of the middle class, or poor? What type of costume does he or she wear? Is the costume formal, semi-formal, or casual, and is the fabric silk, satin, velvet, synthetic, or cotton? Are properties (props) involved? If so, what are they? If the central character is male, does he wear a hat, a scarf, a necklace or other jewelry, a cape? Does he carry a cane or smoke a cigarette, a cigar, or a pipe? If the central character is female, does she wear makeup? In what style is her hair done? Does she wear a hat, a scarf, or jewelry? What kind of purse does she carry? Is it large or small, expensive or economical? Does it match the rest of her outfit? Do her shoes have high heels? Are the pumps? Are they flats? Is she wearing tennis shoes or sandals? Does she smoke? What other props are shown in the picture? Are there cars, a beach, mountains, a sunset, posters, a bottle of whiskey, beer, wine, or champagne? Is there food? Where is the model or models? In a restaurant? At a resort? In a living room? In a bar or nightclub? In a bedroom? In a bathroom? In a swimming pool? On a highway? In the mountains? In a desert? In a jungle? What does the advertisement’s setting suggest about the central figure’s values and lifestyle?

Answer the same questions with regard to the secondary, or supporting, figures in the advertisement. Also consider how they are related to the main figure. Are they equals? Subordinates? Are they of the same sex, the opposite sex, or are they in mixed company (both males and females)? Is the central figure the same age, older, or younger than the other models? Do their expressions suggest the type of relationship they share? Is it romantic? Competitive? Friendly? Parental? Dependent? How would you characterize their relationship and why?

Readers read from left to right and from top to bottom, and, in general, viewers are apt to do the same. People also remember best what they hear or see last. Next, they tend to recall better what they hear or see first. What they see or hear in between is remembered least. Artists use various techniques, but chiefly contrast, to move the viewer’s eye, or gaze, across the “canvas” of the page. Where does one’s gaze enter the picture? What pathway does it follow as the viewer considers the advertisement’s picture? Where does the gaze pause or double back for a second look before continuing? Where does the gaze end? In what order were the objects and other elements in the drawing or the photograph encountered? Was a relationship among them of some kind suggested? If so, what and how? (Pay particular attention to contrasts.)

Consider the text. Is it a paragraph? A sentence or two? A phrase? A single word or a series of words, each of which is capitalized and punctuated as if it were a sentence? Is the style formal or informal? Is the language scientific, professional, or scholarly, or is it the language of everyday speech as used in ordinary discourse? Does the text contain jargon (highly specialized vocabulary used to communicate specialized knowledge) or slang? Is it original or trite? Colorful or plain? What types of figures of speech (allusion, hyperbole or exaggeration, irony, metaphor, parody, personification, pun or play on words, quotation, reification, sarcasm, satire, simile, symbol, synecdoche, understatement, zoomorphism) does the advertisement’s text employ?

Consider the advertisement as a whole. What is the dominant emotion it seeks to convey? What basic metaphor does it suggest? What pun or play on word occurs in the text, and how does it relate to the advertisement’s picture? What type of product or service does the advertisement sell? To whom does the advertisement seek to sell the product or service? (Hint: the viewer is supposed to identify with the central figure in the advertisement.)

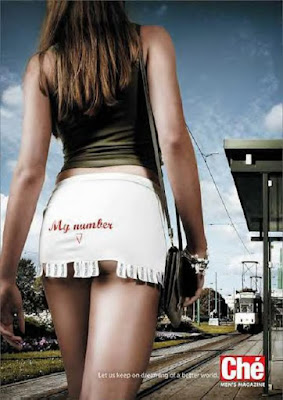

Here is an example of how to use these techniques to read an advertisement. This advertisement, which appeals to men of the same approximate age as its female model, shows a young woman from behind, as she walks along a trolley station. Her face is not shown. Therefore, the emphasis of the picture is on her body, rather than her face, on the physical rather than the personal. She is an object, rather than a person. She is dressed very simply. She wears a simple, green top that exposes her midriff, a charm bracelet, and a white mini-skirt. A small, simple, black purse is slung over her right shoulder.

She is the largest object in the picture, and she is the closest to the image’s center, her positioning within the picture, like her size, emphasizing her over everything else that is depicted in the advertisement. Next to the figure of the young woman herself, the most outstanding prop in the picture is her skirt. It is short enough to reveal the lower portions of her buttocks, which are bare, suggesting that she either wears a thong or no underwear at all. The exposure of these parts of her anatomy draws the eye, as does the apparent fringe that adorns the bottom of her skirt, some of the tassels of which are missing, revealing the parts of her buttocks that show.

There is something else odd about the fringe: the tassels, which are short, rectangular strips, bear printed text that is too small to read. However, on the seat of her skirt, in red cursive lettering, below which is an arrowhead, pointing downward, is the message, “My number.” This message makes it clear to the advertisement’s viewer that the text printed on the tassels identifies her telephone number. Her skirt is itself an advertisement of the sort that includes, along its bottom edge, a series of tags that are printed with a telephone number to which those who are interested in the product or the service that the advertisement promotes may respond. Essentially, the model is saying, to all interested parties, “Call me.” It is based upon a play on words, alluding to the common phrase, “I have your number.”

The accompanying text at the bottom of the advertisement, which is printed in smaller font than the message on the model’s skirt, indicates that the image that the advertisement creates--of a nubile young woman who is available to anyone who is interested in calling her--is a fantasy: “Let us keep on dreaming of a better world.” The advertisement has a playful tone, suggesting that the “better world” to which it alludes would be a fun place to be, and the fun would be of a physically intimate variety. Following this fine print, as it were, is the logo that identifies the product that the advertisement is selling,

Ché, a “men’s magazine.”

The model seems to represent the sort of fantasy girl that the magazine is apt to feature on a routine basis. By purchasing or subscribing to this magazine, customers gain admittance to the “better world” of fun-loving, available dream girls. The train represents opportunity. The model is approaching the station. If the viewer were present, he might meet her, and, if he were to join her on the trolley, the train might convey him--or, rather, him and the young woman--to a common destination. The silent text of the advertisement seems to be. “Don’t miss the train!” and represents a call to action, or, in the language of the trade, the closing sales pitch.

Next: “Luann”